How many times have you watched a film and when the credits rolled felt so good about life that an overwhelming urge came over you to clench a fist and throw it around in the air as if you yourself had overcome the hero’s adversity? This is the power of great storytelling—to move the viewer’s mind into an altered state of consciousness, detached from its immediate surroundings, suspended in a dreamlike state, playing surrogate to the emotional and psychological torment of the characters we see onscreen. When the hero struggles, we struggle, when they triumph, we triumph.

You can experience this phenomena by watching any decent film, but one tiptop example can be had with the 2009 film, Balls Out: Gary the Tennis Coach in which we see Seann William Scott portray a washed up tennis pro living contently in a recreational vehicle and teaching the racquet game to a bunch of high school misfits who find themselves making a run for State Champion against neighboring school, South Point High.

At first glance, the film feels like every other underdog sports comedy regurgitating the same predictable script and climactic ending told a thousand times before—The Bad News Bears, The Mighty Ducks, Major League, and so on. However, in each retelling of this story the need for novelty increases as filmmakers must find new and unconventional ways to keep the audience surprised and interested. In Balls Out, the comedy axis is moved into strange new territory as all political correctness is forgotten, the racy comedy filters removed, the comical quirks embellished, and the bizarre verbal quips turned back up to allow the characters—the tennis coach in particular—a return to their more authentic self, laying bare the gutsy, gritty soul of modern man.

In this raw and unfettered honesty, a pinnacle is reached towards the end of the film when we hear a 5-year old girl in the grandstand shouting words of encouragement at our tennis hero who has fallen because of a pulled muscle, “Mike, you bitch! Get up and rip this motherfucker’s butt open! And make him lick his own shit off your huge fucking cock!” Heads turn and everything grinds to an abrupt halt. The crowd is stunned by the hot, venomous profanity spewing forth so masterfully from this adorable, little child. The widowed father quickly throws up his palms and offers an excuse for his daughter’s surprising rancor, “She really misses her mother.”

Yea, yea, yea; profanity, I get it. It’s filthy and rude and holds no place among the polite and courteous gentle men and women we all describe ourselves to be. But all this cussing, cursing, and swearing plays such a crucial role in society that it’s hard to imagine a world without it. The word fuck, for instance, is so versatile in its utility that the entire range of human emotion can be expressed through the shape and almost infinite forms of inflection this four-letter word can take. We let go, celebrate, lament, wonder, seduce, frighten, soothe, and insult our fellow man simply by decorating our prose with this easy-to-deliver syllable.

Swearing is an art form. You can express yourself much more exactly, much more succinctly, with properly used curse words.Coleman Young, former mayor of Detroit

Unfortunately, not everyone sings this same praise. Some people don’t swear at all or will even sensor it out of television and film with bleeps and word substitutions because they somehow believe their morals are better than the rest of ours. Yet, all these pretend words—fudge, crap, shoot, and ding-dong-diddly—are just verbal euphemisms that carry the same weight. The only difference is in our collective delusion in eyeballing some as being heavier than others. And that’s a crying shame because there is a need for swear words now more than ever.

Every day we run into more and more circumstances where frustration, despair, pent up rage, and bitter disappointment rattles our calm character and shakes loose any number of expletives that materialize from the rough seas of everyday living. But there are times when our rain of profanity is so thick and heavy that a concerned citizen might feel compelled to ask, “Woah there little buddy. What’s the cause for all this colorful language?” And there may be several different reasons as to why, but the one thing that makes us swear far, far more than anything else in this world is the people! People annoy the fucking bejesus out of us. So much so that we can sum up any societal problem simply by shaking our heads and breathing out, “Fuckin’ people…”

Our Place in Time

Every time we turn on the news or scroll through social media we can’t help but notice a growing movement that has taken the world by storm—a grand civic derangement that has people behaving and thinking in ways that have become increasingly stupid, feverish, and outright moronic. Examples are found everywhere: a 2017 survey revealed that over 16 million Americans believed chocolate milk came from brown cows. In 2020, “Mad” Mike Hughes died after crash-landing a homemade rocket during a failed attempt to prove the world was flat. Also in 2020, social media influencers, Ava Louise and Larz filmed themselves licking toilet seats in a game that no one else wanted to play. In 2021, a man urinated on the counter of a Dairy Queen after being asked to wear a face mask to reduce the spread of covid-19. The list goes on ad infinitum, and the only response we have to give is to shake our heads and say, ”Fuckin’ people…”

Before I do anything, I ask myself “Would an idiot do that?” And if the answer is yes, I do not do that thing.Dwight K. Schrute, Assistant to the Regional Manager, Dunder Mifflin

Future generations will look back at this time in human history as the Golden Age of Stupidity. Never before have we had access to so much knowledge and information while, at the same time, having no idea how to put it to good use. Sloth, negligence, incompetence, and cluelessness are the key performance indicators that define our current philosophical era—behaviors that never cease to amaze, no matter how used to them we become.

Licking toilet seats is a game that no one wants to play.Ava Louise, the peach.

When faced with a difficult or uncertain situation, people don’t take the time to question, consider and evaluate information, or look up any empirical evidence that might prove useful to their thoughtful analyses. They ask themselves easier, more favorable questions, and answer the substitutions instead. People get hung up on their feelings and ignore facts that make them feel uncomfortable. Mental shortcuts are chosen and poor decisions made.

Various causes have been given to explain how we arrived at this point in history. Some point fingers at specific people, institutions, or technology as if the problem could be solved through the removal or replacement of such things. But social problems are inherently difficult to fix and never as easy as flipping a switch. And so, we must question if these nuisances are just symptoms and not the disease itself.

In his 1971 book, The Human Zoo, Desmond Morris puts forth a more elaborate thesis on the human condition, drawing similarities between the aggressive, sexual, and parental behavior of animals held in captivity and deviant human conduct that manifests under the pressures of urban living—that being outside of our natural habitat primes us for social instability and erratic behavior. As always, Morris’s ideas are thought-provoking, but they may only be part of the right answer. We always have to wonder if people, in general, just don’t know how to think. At home, in our schools and churches, and everywhere else people are taught what to think, but never how to think.

Given the barrage of issues that we’re forced to deal with as persons and as societies, about health, illness, justice, war, religion, sexuality, identity, and whatever else, wouldn’t it be great if people, in general, could develop a better understanding of how to think in order to form better opinions, arrive at better solutions, and to become, perhaps, less wrong about themselves and the world they inhabit? This idea should strike anyone as both interesting and important as our ability to reason is so often the pedestal on which we stand to view those around us.

Man urinates on counter to prove a point (We’ve all been there).Dairy Queen, Port Alberni, BC

Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Kahneman!

In order to improve our ability to think and reason it’s probably best to seek out the advice of someone who studies this stuff for a living. Perhaps an eminent psychologist who’s made valuable contributions to the field of rationality and human decision making. Daniel Kahneman is one such character.

In 2013, Kahneman condensed a career of studying cognitive error into a 500-page book called, Thinking, Fast and Slow, where he rambled on about the dual-process model of the brain, System 1 and System 2, which produce fast and slow thinking, respectively.

System 1 operates on autopilot, involuntarily, and with little effort or sense of control. It’s fast because at its core, System 1 is the result of associative memory. It maps connections between words, images, emotion, feelings, ideas, and memories to build an interpretation of life without us really having to think things through, like when we jump to conclusions or go with our “gut” instinct. That’s not entirely bad as humanity wouldn’t be here today without it.

System 2 is the high achiever. It performs under the heightened experience of agency, choice, and concentration. It uses a lot of energy and focused effort to work through problems before arriving at decisions. Under ideal situations, System 2 is a self-criticizing and self-correcting miracle of evolution, but it’s painfully slow and tires easily, and so it usually just accepts whatever System 1 is telling it. This is the problem, and in his book Kahneman explains how we often believe our decisions are the result of logical and coherent thought processes employing the full capacity of System 2 but in reality, System 1 is where we spend most of our time, which wouldn’t be such a bad thing if it weren’t for all the defects, glitches, and flaws that guide our ruminations.

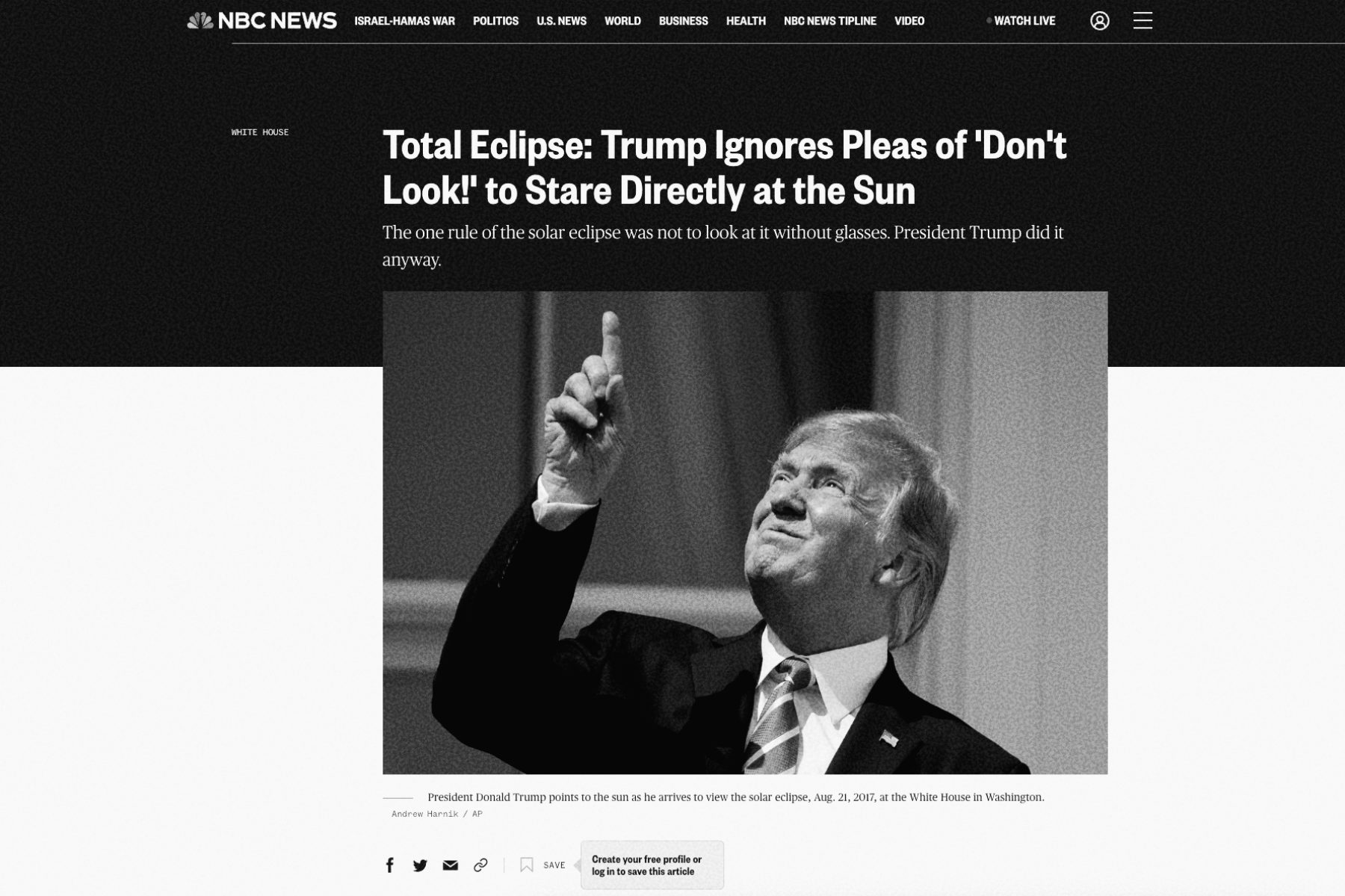

U.S. President, Donald Trump, stares up at the Sun after being told not to.The White House

Systematic errors, known as cognitive biases, obstruct the brain from processing and interpreting information correctly. They thwart our ability to make sound judgements by warping our perception, like when we only watch news stories that confirm our opinions (confirmation bias), or when we rely too heavily on the first piece of information we hear (anchoring bias).

Psychologists have identified over 180 biases that influence how the mind constructs its own subjective reality. Biases shape how we behave, think, and interact with the world around us. They are a part of how humans think, being a chemical and biological process in the brain, not a kind of cultural defect that arises from a poor upbringing or being uneducated.

Towards the end of his book, Kahneman asked the question, “What can be done about biases? How can we improve judgements and decisions, both our own and those of the institutions that we serve and serve us?” Despite decades of studying how the brain worked to improve his own reasoning, Kahneman concluded he was still prone to error, “Except for some effects that I attribute mostly to age, my intuitive thinking is just as prone to overconfidence, extreme predictions, and planning fallacy as it was before I made a study of these issues.”

Kahneman had improved his ability to recognize situations in which cognitive error would be likely but he wasn’t able to do much to prevent them from happening. And sure, we can turn on System 2 and focus intently on our perception, but as soo as our mind gets tuckered out, it defaults back to System 1. But when a psychologist fails to overcome his nemesis, what does that say for the rest us?

However we choose to look at it, cognitive bias is the hero in this human comedy. We cannot snip it from society and make the world a more reasonable place. Civilizations rise and fall, guided by our hero’s ambition. Politicians create and abolish laws, championed by our hero’s plight. Society stumbles along, in excess and in tension, being pushed and pulled, constantly surprised and turned upside down by the hero of our story.