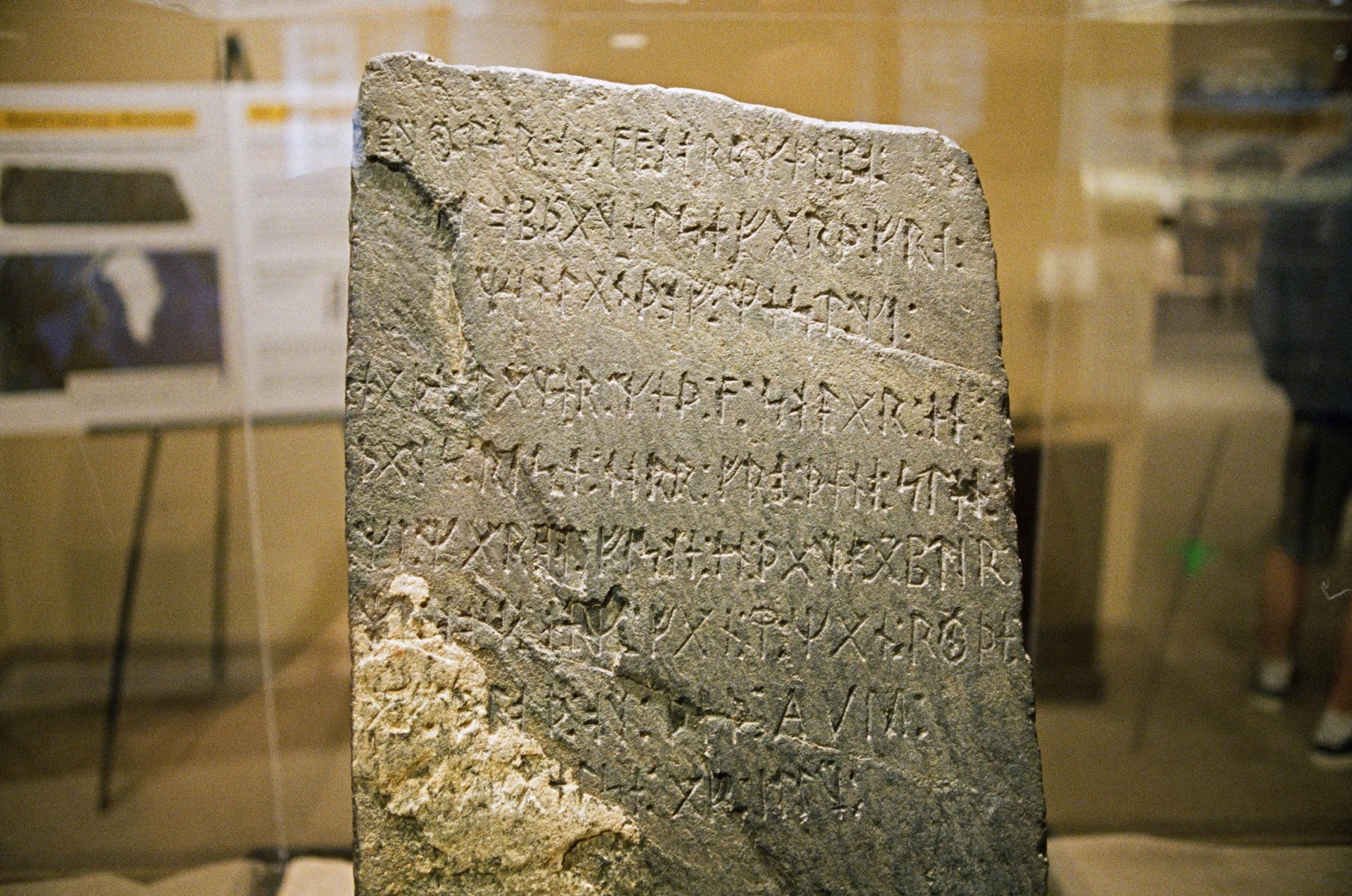

The story goes something like this: One fine summer day, back in 1898, an immigrant farmer, alliteratively named Olof Ohman, was out clearing his land from stumps and trees near Kensington, Minnesota when he discovered a 200-pound stone tablet containing what appeared to be ancient Scandinavian runes. The inscription, as it was later translated, told of an ill-fated excursion led by Viking explorers westward from Vinland. Chiseled at the end of the message was the date, 1362.

Upon hearing of such an out-of-place Viking artifact, discovered deep in the heart of the North American continent, our initial reaction should be to blurt out Bullshit! in such a long and drawn out manner that any notion of Minnesotan runes would be so wildly preposterous that it wouldn’t even deserve a well-mannered and dignified response. But just to be sure, a copy of the inscription was made and sent to several universities in the United Sates and Europe for scholarly analyses by those familiar with this sort of thing. And within a year of the stone’s discovery, the inscription was unanimously declared a hoax.

There are 10 men by the inland sea to look after our ships fourteen days journey from this island. Year 1362.

Undeterred by expert opinion, there remained a small community of people, bewitched by the magic of runes, who would spend their life searching for evidence to prove the carvings were real. Quite honestly, the question of authenticity has always been contested like a lopsided boxing match between amateur historians, such as Hjalmar Holand and Scott Wolter, swinging American anti-intellectual populism in one corner and nearly every admissible expert stiff arming with linguistic, geologic, archeologic, and historic scrutiny in the other.

Centuries-old runes always conjure up feelings that some ancient or hidden wisdom is being passed to future generations. But can human feelings alone stand in as evidence?Alexandria, MN

The language of the runes is flaky from all sides. It’s cross contaminated with modern Swedish and Norwegian, and marred with inconsistent spellings. Some symbols died out several centuries before while others have parallels with eighteenth and nineteenth-century runes. The wear and edges of the runes look more like a recent carving, not something analogous to a 14-century date. The date, 1362, is much too late. The Viking explorations had pretty much run their course by then. All of this and more led runology experts to dismiss the stone as a modern reproduction by someone who had a scant understanding of runes and of the English language.

But rhyme and reason will never account for the cultural and religious factors that fueled the stone’s survival. And so, Minnesota’s favorite myth becomes a helpful lens through which we study pop culture and American civil religion, which is fine, because the cult that surrounds the stone will always be more fascinating than the chisel work itself.

Historian and author, David M. Krueger, studied the stone extensively from this anthropological perspective and has even gone so far to say, “It’s disturbing that, on one level, Americans are only interested in pre-Columbian North American history if white people are involved.” In his book, Myths of the Rune Stone, Krueger describes the stone as a powerful civic myth of origin, as a source of ethnic pride, as a heroic Christian sacrifice, and a justification for the violent conquest of the region’s first residents, as well as a useful tourist attraction to bolster the local economy.

For a nominal fee, visiters can admire the runestone and early frontier history at the Runestone Museum in Alexandria.Alexandria, MN

Ultimately, the rune stone’s story exemplifies the demarcation between the things people want to believe and actual facts. Regardless of how hard we wish Minnesota Vikings existed, the runestone is still just a nineteenth-century fabrication. Had its author known more about the history and the language of his champions, he could have created something much more convincing. As it sits now, the Kensington Stone doesn’t pass as quality workmanship when you measure it against other, more successful, attempts at tomfoolery.

A History Of Romantic Ideas

Hoaxes have a rich and decorated history of creative individuals testing the limits of human rationale. The scope of these shenanigans have no single domain of deception and range from the trivial, like manipulated photographs, to extravagantly orchestrated efforts as seen with the Cardiff Giant. Some hoaxes are motivated by malicious or monetary intent while others are merely thought-provoking experiments. And while some hoaxes can be boring and easy to dismantle there are, however, some examples that stand out from the rest.

The Kensington Stone. If it could talk, what would it tell us?Alexandria, MN

In mid-century America, the art world became obsessed with abstract art. This was the kind of expressionistic mess seen in the works of Jackson Pollock and Franz Kline—no careful brushstrokes or delicate use of light, just drip and throw paint haphazardly onto the stretched canvas. Then, hang the work in the finest art galleries and make declerations like, “The artist draws a balance between chance and calculation in a bold reflection of life itself, the gestural creation resonates with passionate emotion and the breadth of the human experience,” — or some other bullshit like that. It was only a matter of time before some wry bastard decided to mock this sloppy technique and the culture that surrounded it.

In 1964, the Gallerie Christinae in Göteborg, Sweden held an exhibition to showcase new works by avant-garde artists. On the night of the exhibit, everyone was fascinated by a set of paintings by a previously unknown French artist named Pierre Brassau whose work was definitely in the abstract. Rolf Anderberg, an art critic for Göteborgs-Posten, was so moved by Pierre’s talent and that he remarked, “Pierre Brassau paints with powerful strokes, but also with clear determination. His brush strokes twist with furious fastidiousness. Pierre is an artist who performs with the delicacy of a ballet dancer.”

The Olof Ohman farm house lies southwest of Alexandria along County Road 103 and is now part of the Runestone County Park.Alexandria, MN

Pierre was actually a four-year-old chimpanzee named Peter from the Borås Djurpark Zoo. A tabloid journalist, Åke Axelsson, at Göteborgs-Tidningen had grown tired of seeing people ooh and aah over daubs of paint being thrown down and celebrated as if it were a Michelangelo. So he convinced a zookeeper to let Peter mark up a few canvases to see whether art critics could distinguish between the work of an accomplished artist and that of an animal. Turns out, most critics had fell for the stunt.

Another ruse took place in 1985 when Sports Illustrated Magazine ran an article about an eccentric mystic named Haydon (Sidd) Finch who was supposedly deciding between a career in baseball and one playing the French horn — a difficult decision for sure. Sidd was said to have used an unusual pitching style, kicking his leg skyward like Juan Marichal and following through with bodily contortions resembling Goofy from Walt Disney’s short film, How To Play Baseball — all of which had been acquired in Po, Tibet where Finch had learned the method of siddhi, the yogic mastery of mind-body, which enabled him to throw pitches with blazing speed and accuracy. At the New York Met’s training camp, the team’s radar gun clocked Sidd’s fastball in at a violent 168 mph. Bob Schaefer, manager for the Mets’ AAA farm club, said Nolan Ryan’s fastball (106 mph) was like a change-up compared to what this hot rookie could fire.

If he didn’t have this great control, he’d be like the Terminator out there. Hell, that fastball, if off-target on the inside, would carry a batter’s kneecap back into the catcher’s mitt.Davey Johnson, New York Mets manager on Sidd’s throwing ability

Of course, you have to know something about professional baseball to find the humor in this, but the idea that anyone could throw a baseball 60 mph faster than the best MLB pitchers of the day was total bullshit. Yet, many people, including those working professionals in baseball, believed Sidd really existed. The major networks, ABC, NBC, and CBS, all sent reporters to the Met’s training camp to follow up on the story. Baseball commissioner, Peter Ueborreth, was questioned over whether other teams’ players could face Finch safely. And Mets fans flooded Sports Illustrated with requests for more information. Hardly a soul noticed that the SI issue was an April 1st edition.

Then in 2014, Huvr Tech, a small startup, launched a website and video claiming they had built a working hoverboard, just like one seen in the 1980s film, Back To The Future, and they would be releasing it soon to the public in several different color options. Celebrity appearances in the video included Tony Hawk, Moby, and even the “Doc” himself, Christopher Lloyd, which seemed to add even greater credibility to the gravity-defying product—as any celebrity endorsement should do. But in the end it was all just another elaborate hoax conceived by the clowns at Funny or Die.

The only way to assert the authenticity of Minnesota's runestone is to create a giant replica of the thing.Alexandria, MN

How is it that we fall to hoaxes so easily? Is it because we’re too excitable by the novelty of the unorthodox, the curious, the amazing? Sure we are. We love to be tickled by new ideas, to be fascinated and enthralled by things that ought not be. It’s that unexpected moment of discovery that ignites our spirits and compels us to share it with others.

At some superficial level, however, the answer also rests on the relationship between science and society where our beliefs and opinions form through the precarious imbalance between inquiry and reason and the romantic ideas that align with our primate biases for emotional pleasure, especially when the hoax confirms our previously held hopes and dreams. Confirming one’s beleifs through mis- or false information cannot be overstated because it’s this very crux that defines the holistic worldview that drives humanity’s collective decision-making.

It’s not all bad, many of our convictions, beliefs, and opinions are carried with some degree of sincerity and benevolence. But if humanity wishes to move forward, as it always claims to want to do, then we must find a way to deal with hoaxes outright because as along as hoaxes, myths, and chicanery exist so does our wrestling with truth and knowledge.

A Bullshit Detection Kit

In his book, The Demon Haunted World, the cosmic sage, Carl Sagan, devoted a whole chapter to the many types of deception that society is most vulnerable to — from psychics and religios zealotry to the paid product endorsements by scientists. But he reminds us too that falling for such fiction does not make us stupid or bad people, just that we need better tools of judgment. So he defined a set of nine rules to be wielded as healthy skepticism as a sort of Bullshit Detection Kit, if you will. To summarize:

- There must be independent confirmation of the “facts.”

- Encourage substantive debate on the evidence by knowledgeable proponents of all points of view.

- Arguments from authority carry little weight.

- Spin more than one hypothesis.

- Try not to get overly attached to a hypothesis just because it’s yours.

- Quantify. What is vague and qualitative is open to many explanations.

- If there’s a chain of argument, every link in the chain must work (including the premise) — not just most of them.

- When faced with two hypothesis that explain the data equally well, choose the simpler.

- Always ask whether the hypothesis can be, at least in principle, falsified.

By adopting these deterrents of falsehood responsibly we become better equipped for dealing with the real world. And the more frequently we apply these rules to everyday living the more likely they become habit, then culture, then adopted by our education system. How different would the world be if instead of standardized testing school children were forced to master a Bullshit Detection Kit and to idolize the gainful pursuit of asking questions? It would be amazing, especially to sit in a room full of third graders and hear one of them say, “No, no, no, no, no. That’s bullshit, and here’s why…”

It’s okay to fool people as long as you’re doing that to teach them a lesson, which will better their knowledge of how the real world works.James Randi, magician and challenger of the paranormal

But if hoaxes are motivation to acquiring better tools for things like critical thinking, asking questions, and mindful deliberation, doesn’t that make them beneficial? Shouldn’t we encourage pranksters, tricksters, and dirty rascals to hit us with their best shot? A worst-case scenario is a world that only asks us to use our toolkit sparingly, or one that tries to rub out hoaxes altogether. Our ability to examine and investigate would be so undercooked it would be like throwing a frozen chicken onto the kitchen table and then yelling upstairs at the kids, “Supper’s ready!”

The 28-foot viking statue, Big Ole, audaciously declares Alexandria as the birthplace of America, ignoring all historical fact and the peoples already living here.Alexandria, MN

A well-conceived hoax is not just a celebration of creative expression but also the opportunity for thoughtful investigation. Hoaxes better prepare citizens for careful reasoning and thus better preparation for life. Hoaxes can be a riot of fun. We should all glorify a good hoax. They are the seeds that germinate critical thinking, and I can’t wait for the next one.