Human beings naturally resist change and in their ego-driven hallucinations will seek out static immortality in a world of perpetual change. Odd, isn’t it? Whether we’re bewitched by the promise of anti-aging creams, or drugged by visions of an afterlife, preservation of the self is the tastiest carrot-on-a-stick that we chase. We live for today and wish for it to last forever. But in our refusal to acknowledge the passage of time, we cannot help but overlook the many curious questions that arise from the business of our unavoidable future.

Is it cheating if we merge artificial components with our biological form? If by prolonging our existence of being alive, does that, somehow, take away from our time of not living? If reality were just an experiment of consciousness, why go to the bother of extending it? If there really is an afterlife, cannot we deduce then, by way of the same philosophical proof, a before life?

Death is sometimes tragic, sometimes terrible, to choke out one final breath and be sucked into the dark abyss of nothingness. At least, that’s how death is perceived by the general masses, but for those who believe in the afterlife, there’s only one question that need be addressed: What the hell? How can we compare such a brief moment of living to the ever-after of all eternity? How selfish, self-centered, self-absorbed is it to mourn the loss of a loved one at a funeral when you know full well they are “kickin’ it” up in a better place. Are we to obey the laws of Nature, or must Nature bend to our every desire?

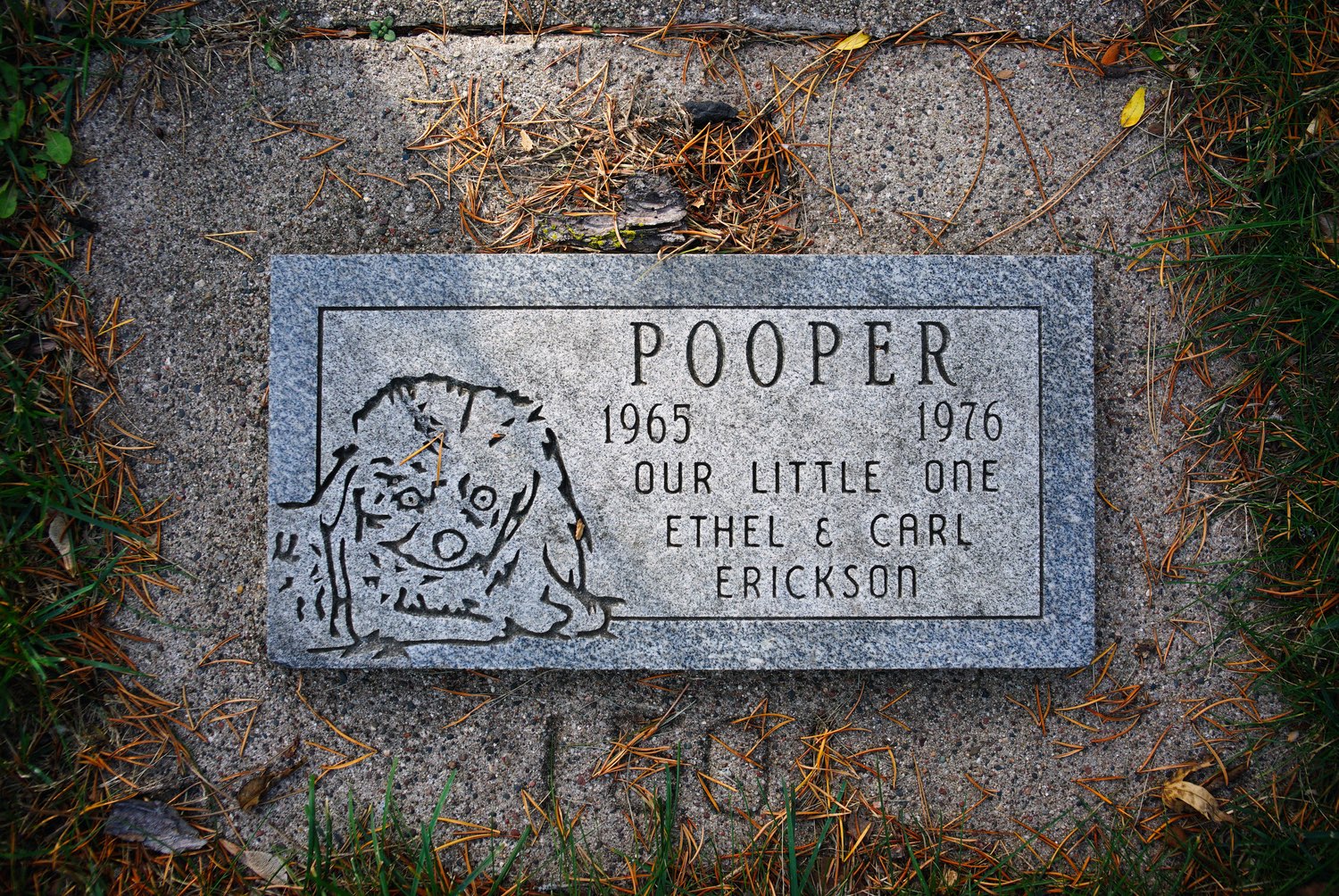

The Memorial Pet Cemetery in Roseville, Minnesota are were pets like Juan Jose are kickin' it in a better place.Roseville, MN

A human life occupies the briefest span of time in the annals of everything. Even for the person who has filled each and every day for 100 years with meaning and purpose, life is still just a mere transitory experience—a fart in the wind—from the time we’re born to the time we’re pushing up daisies.

Funerals are not a time and place for tears and colorless attire but a celebration that deserves confetti poppers, glass clinking, and all manner of cheap party supplies, for at that moment of collective remembrance our loved ones have ascended the dirty entrails of the material world and have gained true freedom. No longer chained to the burden of pain and suffering, the deceased are now residing peacefully, up in the clouds, under a double rainbow. It’s basically the same world as seen in the children’s television show, Care Bears.

To die will be an awfully big adventure.Peter Pan, the boy who wouldn’t grow up

But hold on now! Don’t go running out the door in search of a quicker death. We cannot be so careless as to swell with jealousy from another’s happy circumstance—just that we should await it calmly and cheerfully as a kind of peaceful serenity born from steadfast reason.

Death is the common fate, the one universality that all material things share, and if we dive into the history of great thinkers—Socrates, Plato, Seneca, and many others—all contemplating life’s furthest goal post, we discover that each of them understood the importance of learning how to die as a way of accepting this consequence of living. The idea may sound unappealing at first but learning how to die is really no different than learning how to live. By accepting our past and future states we allow ourselves to be more present in the now. We become more aware and attentive to the present. Our thoughts, and actions, and behaviors are all reshaped into greater focus and resolve.

The cemetery offers visitors a curious view into what pet owners name their furry little friends, like Merry Christmas.Roseville, MN

The complication here, as is always the case, is that learning how to die takes time. Who has the time for reprogramming the mind to think differently about our closing curtain? This modern world wants easy fixes. We’re addicted to finding shortcuts and copy-and-paste solutions to all our problems, whatever size they may be. Lucky for us, though, there is a shortcut, and it’s delightfully simple. Drugs.

Sprinkle A Little Magic On Your Fear

Cancer patients often play damsel in distress to the villains of psychological wellbeing—anxiety, depression, a fear of dying, whatever. Based on knowledge acquired from television commercials, antidepressants are often viewed as the sure-fire remedy to these all too common symptoms. However, ongoing evidence suggests that antidepressant drugs hardly work at all, and even when they do, they’re still accompanied with all those undesirable side effects, which sometimes includes death. Unfortunately, there are no FDA-approved pharmacotherapies for cancer-related psychological distress that provide patients with effective and lasting results. So it would be nice if we found one, right?

In 2016, the Journal of Psychopharmacology published two papers from researchers studying psilocybin at John Hopkins University and NYU’s School of Medicine. Psilocybin is the magically delicious compound found in hallucinogenic mushrooms. It’s a tryptamine serotoninergic psychedelic that can alter consciousness and manifest highly salient, mystical experiences. The magic happens through the temporary creation of significantly more pathways in the brain, allowing different parts of the mind to communicate much more freely with one another. So profound and meaningful are these states of being that the psychedelic bard, Terence McKenna, once formulated a theory that boldly asserted it was the discovery of magic mushrooms that led to Homo Sapiens' cognitive leap forward from the caveman days of yore and into the forays of language, pictography, and tool usage that characterize modern man today.

Researchers applying the most rigorously controlled trials demonstrated that just a single dose of psilocybin could produce deep and lasting benefits for the mental health of cancer patients terrorized by the aforementioned villains. A transformative attitude improvement was observed by Dr. Stephen Ross, who concluded, “In conjunction with psychotherapy, single moderate-dose psilocybin produced rapid, robust and enduring anxiolytic and anti-depressant effects in patients with cancer-related psychological distress.” Never before in the history of psychiatry has such a substance proved so effective and so lasting. Even at the 6.5-month follow-up, participants were still feeling the benefits of their single, psychedelic trip, with many believing it was one of the most meaningful experiences of their lives.

Humans and animals alike share in a common and unavoidable future.Roseville, MN

Granted, it’s not all fist bumps and shit grins. Hallucinogens can sometimes turn on us, inducing fear, anxiety, and savage panic. Researchers refer to these fudged expeditions into the unknown realms of the mind as “challenging experiences”, but they don’t really exist in clinical studies where participates are screened, prepared, and fully supported. It’s all about being responsible, which could be said about anything we shove down our gullets. But for those of us with a sound mind, body, and sprit, it looks as if psychedelics are an experience worth having.

But there is another consequence of ingesting psilocybin that has far greater implications than just a little existential therapy. Researchers have also noticed, and taken a liking to, the fact that psychedelic drugs produce a temporary dissolution of the ego. During their groovy trips, psychonauts swap their sense of personal identity, pride, and individualism with a profound sense of connectedness, a feeling of being “one” with themselves, humanity, and the Universe.

The Perfect Gateway Drug

Our everyday mind sees the world as composed of individual components, detached and unrelated from one another. And yet, at the same time, there’s a contradictory belief lurking in parallel, that everything in existence is part of the same fundamental entity, substance, or process. This unique belief structure doesn’t hide out as some obscure ideology about how the world works but appears in many philosophical, religious, spiritual, and scientific perspectives throughout history.

In the 2004 film, I ♥ Huckabees, an existential detective, played by Dustin Hoffman, explains the idea of oneness to his patient, Albert Markovski, played by Jason Schwartzman, through the use of a blanket analogy. Imagine a blanket that represents all the matter and energy in the Universe. Different locations on the blanket are meant to represent different things, like the Eiffel Tower, or a war, or a museum, or an orgasm, or a hamburger. The lesson learned is that we are the blanket, connected, and while surface appearances might appear differently, everything is essentially the same.

We are all one. And if we don’t know it, we will find out the hard way.Bayard Rustin, civil rights activist

While the notion of “everything is one”, or oneness, is certainly fun to think about, it might just be a romanticism that’s only suitable for science fiction and philosophical New Age bullshit. But does that matter? Many rhetoricians of philosophical debate have defended the “belief in belief” mantra because of the positive social benefits, like emotional comfort and moral guidance, that these amusements encompass—which is all fine and dandy, but if anyone is really going to lasso themselves to a belief structure to disperse ethics and moral philosophy why not choose the one with the most kinetic goodness?

In death, those who are best remembered are the ones who brought the most joy and happiness to the world.Roseville, MN

Researchers at Duke University conducted a series of studies to secularize oneness and determine what the psychological implications of believing “everything is one” has on our self-identity, worldview, and behavior towards one other.

Participants were asked to rate their belief in oneness and to what extent they connected with such statements as, “Beyond surface appearances, everything is fundamentally one”, “Everything is composed of the same basic substance, whether one thinks of it as spirit, consciousness, quantum processes, or whatever”, “The separation among individual things is an illusion; in reality everything is one”, “I think of the natural world as a community to which I belong,” and so on.

Those who scored higher, believing in oneness, were much more likely to have an identity that extended beyond their individual self and personal in-group. These thoughtful individuals saw themselves as a communal member of a much larger whole that included humankind, life, the natural world, and even the cosmos. Participants who were connecting with oneness were valuing benevolence, universalism, and compassion towards each other much more strongly than those who were religious yet did not believe in oneness. So, it has to be said that for anyone who is serious about advancing human values and creating a more humane society, oneness is the ideal way of seeing the world and that magic mushrooms are, in essence, the perfect gateway drug for bringing about unparalleled, positive social change.