I would imagine people in the future will look back at this point in history and think, “Damn, were those people backwards back then,” not to degrade the decencies of modern society as a hodgepodge attempt at creating a civilized world but more so as an honest observation. Why? Because progress is incremental. Knowledge accumulates. This is the nature of the world. Like an endless staircase ascending towards greater levels of human understanding, we will always be some place higher tomorrow than where we are today. So, it’s only natural to look down on previous iterations of human society as a “less than” variant.

Today we smile upon those cultures of yesterday who danced for rain, personified evil in black cats, and lacked all knowledge of indoor plumbing. Tomorrow, people will mock us with the same cheeky ridicule. For at no other time in human history has there been more human potential wasted than what we piss away today. It’s as if modern society, in her vast and accumulated wisdom, has acquired pet ideologies for freedom, equality, and human rights, and yet overwhelms herself by laboring over two narrow and short-sighted modes of progress, economic and technological advancement, ignoring whatever consequences these lesser ambitions might have on her more humane desires.

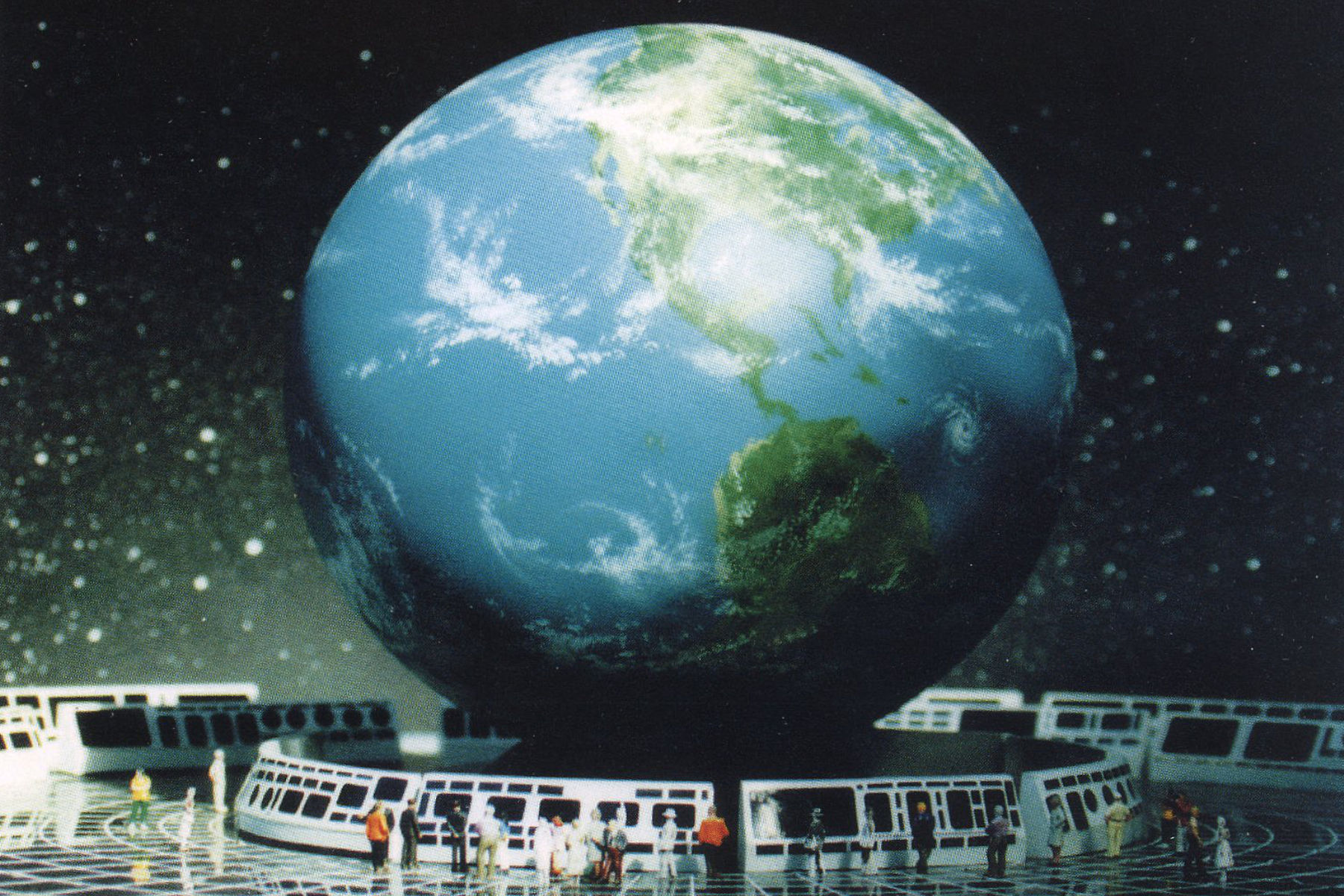

This is more than disappointing because even with our current level of development, humanity has at its disposal all the resources and means to build a just world in which every member of its society can maintain a high standard of living, live a meaningful life, and be treated equally, in all respects, to every other human being. If a magical spell were cast upon the Earth and all inherited biases and cultural norms were removed from the human animal, people would have an affinity towards such things as equality, equal access and the harmony that ensues from the shared use of resources.

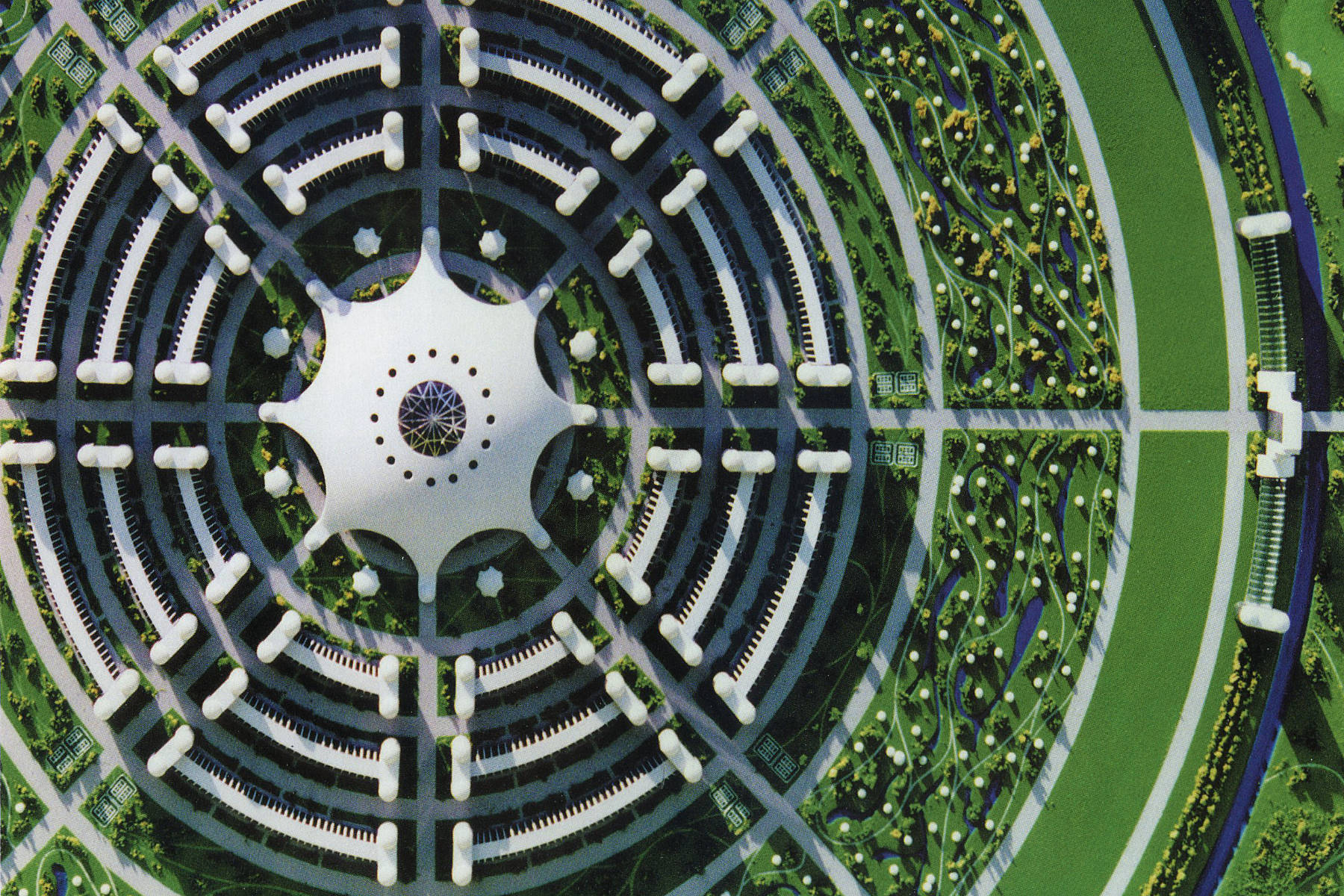

How will future cities and society advance down the road and what will they think of our place in time?The Venus Project

Future generations will learn of their forefathers fumbling around with their frail economic and political institutions and all the obsolete constructs that define our place in time, and they will just shake their heads in embarrassment and confess, “That’s just how it was back then. People didn’t know any better.” But it’s when we reflect on what future societies might say about our predicament that we question how we might improve our way of life. Though, we don’t really need to envision any future criticism because we already have plenty of that today.

Topics relating to social, economic, and environmental problems are covered in a variety of niche publications in physical and digital formats. One such example is Pacific Standard magazine based out of Santa Barbara, California. In the December/January 2018 edition of its print magazine, a cover story titled, “To Get to the Future, You Must Leave the Coast of South Florida”, was published as an introduction to Jacque Fresco’s vision of the future and his non-profit organization, The Venus Project, which sees a future beyond politics, poverty, and war.

To see Fresco’s ideas receiving exposure even in some small, out of the way magazine, was refreshing, but at the same time, it was sort of a letdown as the grander vision of egalitarianism was sullied with cynical skepticism from someone who was only equipped with a passing interest and a partial understanding—the Achilles’ heel of journalistic integrity, actually.

In order to have any constructive conversation about The Venus Project we must first understand what it is and what it isn’t, because the future will always be radically different when compared to its clumsy past, and people will always pass judgement to any societal change as just another fantastic and unattainable dream that’s so far out of reach that it’s not even worth considering. But what they don’t understand is the fact that we’re already living in someone’s ideological fantasy; it’s just not ours.

A Future By Design

Have you ever heard of the phrase, “Well, back to the old drawing board”? It was first mentioned in a cartoon drawn by Peter Arno and published in the New Yorker in 1941. Arno’s quick and deliberate brush strokes paint the hair-raising moment after a fighter jet crashes into the ground. The pilot is seen parachuting to safety in the background while an ambulance and military personnel rush toward the scene. The engineer, with the blueprints under his arm, turns to leave and says, “Well, back to the old drawing board.” It’s funny because it points out how the mind of an engineer is more concerned with improving the machine’s design and preventing the crash to begin with than worrying about budgetary constraints and the wellbeing of a test pilot. And it’s this essence of character, this strong desire to build something better, that formed the basis for how Jacques Fresco thought about the world.

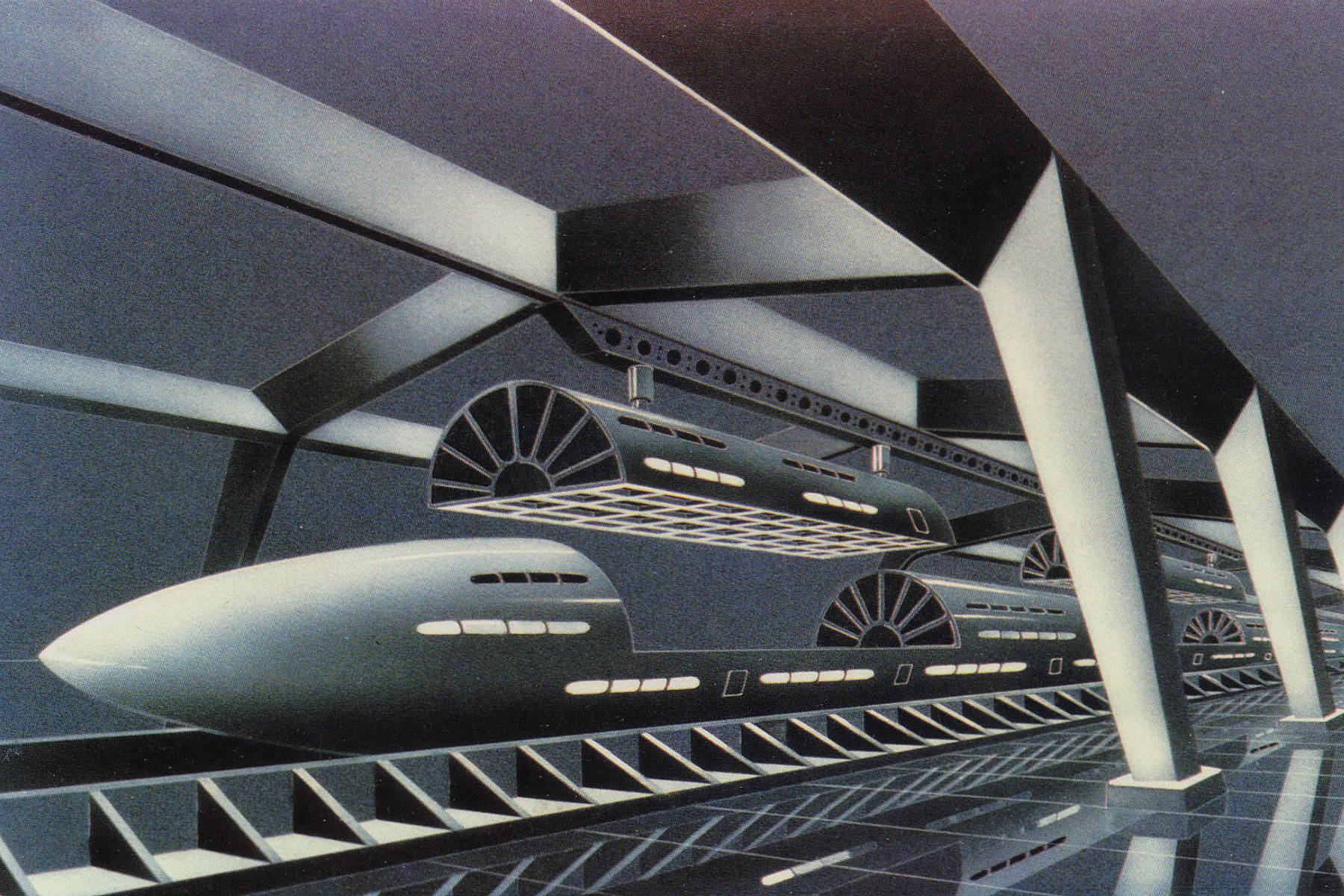

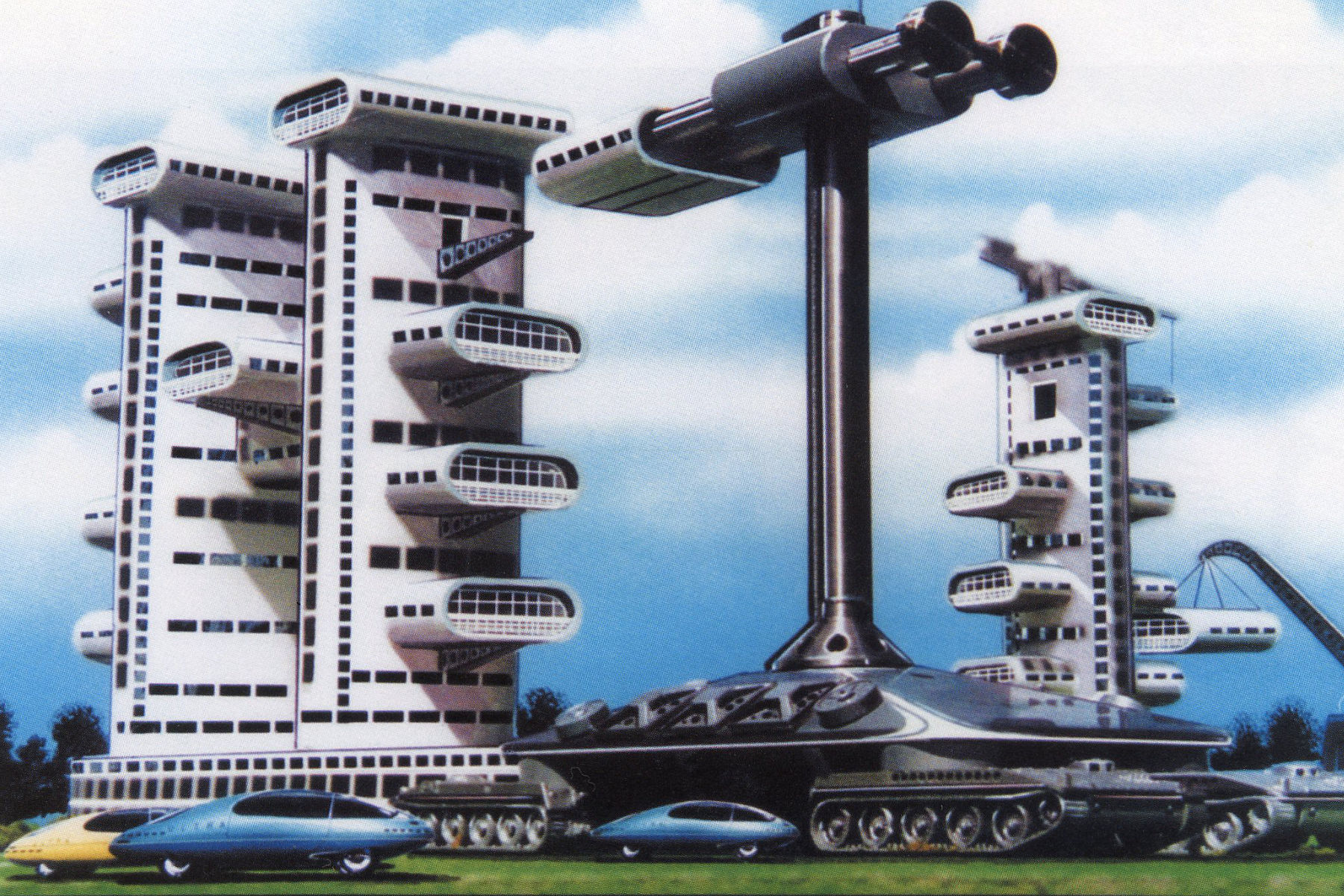

Fresco’s attitude came from understanding science and technology as being iterative. Every time we make a new piece of technology, we do so with the goal of improving upon older systems in order to solve new or existing problems more effectively. Any engineer with a curious and investigative mindset will look at problems in this manner, and they will always have a strong urge to design cities, buildings, and transportation systems that can better serve their purpose—not just as a one-and-done-kind of solution but as part of an iterative and continual improvement process that’s driven forward by the engineer’s curiosity and the need for better answers.

The future cities of tomorrow will be designed to better serve human needs.The Venus Project

But what set Fresco apart from other futurists of his time was his interest in advancing culture and society as well. His social consciousness was particularly shaped by what he experienced during the Great Depression. Despite people being out of jobs, living in squalor and misery, the Earth was still the same place as it was before the crisis. Manufacturing plants were still intact, natural resources were still available, and people were still willing to work, but without the artificial scaffolding of money, people were under the collective delusion that they couldn’t do anything about their situation. Fresco felt the rules of the game were astoundingly stupid, obsolete, and inefficient. If we could use the methods of science and engineering to improve highways, buildings, and bridges, why not use those same methods to improve our social, economic, and political systems as well?

After thinking about the problem, Fresco came up with a system of ideas that could benefit every aspect of human society, from education and economics to politics and planning. In short, he wanted to change existing cultural values into those where war, poverty, debt, and human suffering are viewed not only as avoidable but as totally unacceptable. People are a product of their environment. By creating a better environment for people to live and grow we can change human behavior. Deprivation, poverty, crime, greed, hatred, bigotry, and many other undesirable things can be washed away entirely by establishing a more suitable environment for human beings to live.

Fresco also wanted to do away with capitalism and create a new resource-based economy where all goods and services were available without the use of money, barter, credit, debt, or servitude of any kind. By getting rid of the monetary system and allocating Earth’s resources as a common heritage, people and nations would no longer feel compelled to seek differential advantage over one another.

His system of thought also envisioned circular, fixed-sized cities that could be designed and fabricated as a whole. He wanted to replace boring and repetitious jobs with automated systems. He believed in social engineering as a means to create citizens of a higher community. He wanted to use artificial intelligence and automation responsibly. He had confidence in using computers as a means of governance. He spent most of his life working on his ideas, which he labeled a “Future By Design.” And it’s this kind of gumption that the Venus Project represents—that we can go back to the drawing board and build a better future in which people can thrive and reach their full potential by improving upon what we already have.

Jacques was not a utopian, nor a humanist. He was a person who simply looked at a system or process and wondered how the thing could be improved upon and made better. When asked, “Are you trying to build the perfect society?” he would reply, “I have no notions of a perfect society. I don’t know what that means. I [only] know we can do much better than what we’ve got.”

Mass transit systems could operate more efficiently and more effectively when cities are built responsibly.The Venus Project

Jacques Fresco wasn’t interested in solving all the world’s problems. He just wanted to design and build a better environment to advance all human beings. Once people are free, truly free of debt, obligation, servitude, they can then seek out new horizons that they’ve never even dreamt possible before. Admittedly, this would be the most ambitious task humanity would ever undertake, to reorganize itself to become a better version of itself. But once the need for it was finally recognized, there’s no telling how far humanity would then advance.

The Venus Project probably sounds like complete bullshit. A pipe dream. A mad fantasy from some self-righteous jackass who doesn’t understand how society really works. And it is. But why?

The Price of Our Collective Delusion

It’s easy to latch on to idioms like, “If life gives you lemons, make lemonade.” So brainwashed are people with the idea of just accepting lemonade as their one and only destiny that they’re oblivious to the fact that, you know, you could grow an orange tree and make orange juice if you really wanted to. It’s called, “doing things your fucking self,” and everyone would be a lot better off if we could just throw away empty, heirloom phrases and replace them with more useful affirmations like, “If life gives you lemons, grow a fucking orange tree,” because it teaches our youngsters that they don’t have to be okay with a hand-me-down society conceived in an older and more primitive generation of human ingenuity.

Jacques Fresco’s ideas weren’t anything new. In fact, he pretty much stole all of them. The concept of a “planned” economy was a ripoff of Ludwig Bauer and his 1932 book, War Again To-Morrow, circular cities embedded in nature was nicked from Ebenezer Howard’s 1902 manifesto, Garden Cities of To-Morrow, behavioral modification was scraped from the work of B. F. Skinner, the abolition of property was borrowed from Leo Tolstoy’s 1932 book, What Then Must We Do?, reduced working hours was pinched from Bertrand Russel’s essays on social criticism, and so on.

These critiques and examinations of culture, and the resulting suggestions for future change, are not hysterical shouts from mental patients swatting at dementors but visionary ideas that stand as magnificent testaments to human potential, or at least they could be if we were ever allowed to follow through with any of them. But change is hard.

In his book, The Dragons of Eden, the cosmic sage, Carl Sagan had written, “Human societies are not innovative. They are hierarchical and ritualistic. Suggestions for change are greeted with suspicion: they imply an unpleasant future variation in ritual and hierarchy: an exchange of one set of rituals for another, or perhaps for a less structured society with fewer rituals.”

The future of infrastructure is 3D-printing, automation, and self-erecting buildings.The Venus Project

People are indolent. They prefer to accept, obey, and follow. They have an irrational fear of change and prefer to stick with what they know rather than try the new-and-improved. They fight for the status quo, their particular status quo, with heads down and eyes closed. They think of themselves first and prefer to work themselves into favorable positions before demanding that everything remain the same. This is to say, people are fucking morons, even if they’re just ignorantly playing the part.

That lazy eye, French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, would probably have a lot to say about our unconscious role playing. In his 1943 book, Being and Nothingness, Sartre elaborated on topics such as existentialism, consciousness, perception, social philosophy, and self-deception. But he also identified a particular feature of society that he saw as being ubiquitous with modern life, mauvaise foi, or “bad faith”.

Bad faith happens when we lie to ourselves in order to avoid short-term pain but end up suffering long-term social and psychological impoverishment as a result. Sartre believed we lie to ourselves because we don’t think we have any other options in life—that we’re stuck with what we get. This exceptional quirk in the human psyche affects all nooks and crannies of human thought and judgement.

Sartre provided an example of this psychological deformity by observing a waiter going about his business. The philosopher writes, “His movement is quick and forward, a little too precise, a little too rapid. He comes toward the patrons with a step a little too quick… …trying to imitate in his walk the inflexible stiffness of some kind of automaton while carrying his tray with the recklessness of a tight-ropewalker… All his behavior seems to us a game. He applies himself to chaining his movements as if they were mechanisms, the one regulating the other… …he is playing at being a waiter in a café. There is nothing there to surprise us. …the waiter in the café plays with his condition in order to realize it. This obligation is not different from that which is imposed on all tradesmen. Their condition is wholly one of ceremony. The public demands of them that they realize it as a ceremony; there is the dance of the grocer, of the tailor, of the auctioneer, by which they endeavor to persuade their clientele that they are nothing but a grocer, an auctioneer, a tailor.”

The waiter goes on to tell himself that he is “just” a waiter, that it’s his role in life. It’s his one and true destiny. He had no other choice in life. He had to find employment somewhere. He had to earn his keep somehow. This is just what the universe had to offer. So the waiter goes on to play the part of a waiter not because he believes his actions are the actions of who he truly is but because that is how society tells him how a waiter should behave. Thus, his actions are not based on personal value or belief but are instead an outcome of the external pressure that society places on a person. The mismatch between belief and action is the bad faith.

Instead of hoarding Earth’s resources or creating artificial scarcity, we could share and work towards a better world together.The Venus Project

This cultural phenomena is found throughout every level of our stratified society. People fall into roles they never set out to find. They behave in ways they never saw themselves behaving. But if the individual is so easily funneled into a false and meaningless life then what about society itself? What if capitalism, democracy, a monetary-based economy, elbowing ahead of one another, and behaving like selfish lunatics is nothing but humanity’s one and true destiny? Humankind had to organize ourselves somehow, right? This is just what the universe had to offer.

But nobody wants to hear that. It makes people feel depressed. It says we as a society don’t know what the fuck we’re doing and that we can never exist as anything more than just a collection of squabbling automatons, consumers, and power hungry idiots. So we suppress any insight that hints at we are wasting our lives and our potential. We force ourselves to believe in whatever it is we’re given and stiff arm any suggestion for change because the less we know, the less we’re bothered. The price of our collective delusion, however, is that we close ourselves off to the most important and meaningful opportunities that would improve our lives and in those lives yet to come.